. . . or, How a Long-Forgotten Adventure Module Called Mad Mesa Made Me the Referee I Am Today.

I'm not going to waste time and space on the rationales for including random encounters in a roleplaying game - it's already been done better by someone else, and at this point, most gamers either get it or they don't.

One of the reasons random encounters get shat upon is, to paraphrase, 'wandering monsters are boring and distract from the adventure.' Now, bearing in mind that one of the roles of the referee is to make encounters interesting and integrate them with the setting, if you look only at the tables in, say, a published adventure like In Search of the Unknown - "Orcs (1-4)," "Giant Rats (2-5)," "Berserkers (1-2)" - and applied them uncritically - unthinkingly - by rote - then it's kinda-sort understandable why they might seem boring. However, the random encounter tables in most early sources were far more engaged and integrated with the setting, like the echoing footsteps and settling ruins, the hunting tick and the bandit reinforcements, of The Village of Hommlet. Other games and products ramped this up tremendously, from the fairly sparse on detail but gonzo and evocative Judges Guild's Wilderlands of High Fantasy to the myriad slice-of-life-in-Sanctuary encounter tables in Chaosium's wonderful Thieves World box set to the gold standard of published sandbox settings, Chaosium's Griffin Mountain for RuneQuest. When I've described my approach to running a roleplaying game campaign on different intreweb forums over the years, I've been told many times that it sounds a lot like Griffin Mountain, which was interesting in that I'd never actually seen Griffin Mountain before finding a copy this past year - now that I have seen it, then I can say, yeah, my campaigns are a lot like that.

My original inspiration for random encounter design wasn't Griffin Mountain, however - it was TSR's Mad Mesa for Boot Hill.

Mad Mesa is something of an odd bird. It's a solo module, written in a 'choose-your-own-adventure' format - "6. You are standing on Broadway opposite the north window of building 21. You may go west 62 or east 5." - set in a town on the verge of a range war between rival ranchers. There're intrigues and mishaps, and depending on the player's choices and the luck of the dice, the adventurer can either make a tidy fortune or or be gunned down by one of the factions, or the law. The format makes solo play a bit stilted - 'But I wanna peek in the window of building 21, and then I wanna climb on the roof!' - but it's an entertaining setting full of fun Western clichés. The module includes notes for running it for a group of player characters as well.

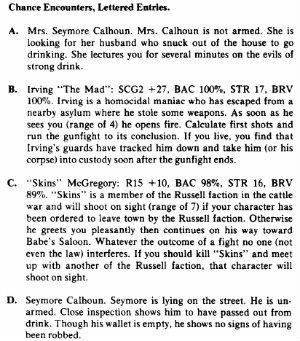

But it's the "Chance Encounters" table that left a lasting impression on me.

First, every chance encounter is with a named individual - no "Orcs (1-4)" - with a distinctive motivation and a brief but revealing backstory - the brash kid out to make a name for himself, the snake oil salesman, the drunk and his temperance-preaching wife. This is, in my experience, what "Orcs (1-4)" should bring to the table, and in the hands if a capable referee, it does, but for some gamers this was a conceptual hurdle they apparently never managed to cross - generic 'wandering monsters' appeared at random and disappeared the same way, with no real connection to anything in the setting. There were certainly many more examples of random encounter tables that were woven into their locations - before I played Mad Mesa, I typically tied random encounters to locations with the adventure site - patrolling guards from the gatehouse, rats from the warren on level 1, Imperial Marines from the Dagger-class cruiser in docking bay 93, a pair of enemy agents conducting surveillance from a panel van. But a big part of what I took away from Mad Mesa's chance encounters was a sense of random encounters as strands in space leading off into the undiscovered portions of the game-world, of implications reaching beyond the immediate circumstances of the locale where the encounter takes place - Irving "the Mad" has nothing to do with the events taking place in Mad Mesa - rather, he is a part of the larger game-world.

Second, several of the chance encounters are integrated into the backstory of Mad Mesa's range war. The player character may run across members of the Russell and Kane factions, and depending on the locations visited in the course of the adventure, the encounter could prove inconsequential or deadly. This created a continuous feedback loop between the chance encounters and the keyed adventure locations - if your character kills Skins McGregory in a chance encounter after being warned to leave town by the Russell faction, then ol' Skins isn't available for the climactic gunfight of the module should your character take part. There's also lil' Joey Black, paperboy for the Mad Mesa Gazette, who for the price of a buffalo nickel can fill you in on the the range war backstory - random encounter as game-world exposition.

What impressed me at age fifteen - and still impresses me today - was how the different pieces fit together in a non-linear way. The chance encounters - and can I add that "chance encounters" as a term of art kicks the everlovin' crap out of 'random encounters' or 'wandering monsters?' - were part of the events of the town, past and present, but they could be presented in a way that didn't require a pre-fabricated plot to unfold for them to make sense. The nature of a chance encounter with Skins McGregory and his Winchester is determined by when the encounter takes place and by the circumstances of the meeting, rather than by a particular order of events necessary to advance 'the story.' What story there is arises from the interplay of encounters.

Random encounters in my campaigns are an important part of the game-world delivery system. They represent the 'living world' which the adventurers inhabit, serving up a variety of unfolding events and chance meetings. When I sat down with the idea of running a cape-and-sword campaign, I compiled a short list of genre tropes appropriate to the campaign. "Coincidences abound" was the second one on my list: in swashbuckling tales, characters run into each other at opportune - and inopportune - moments, so I wanted that to be part of the campaign. The non-linear interaction between site-based encounters and random encounters provides a mechanism for introducing real, dice-driven coincidences into actual play, without the need for dropping a plot-hammer on the players. One such encounter already took place - a chance encounter with a duelist was followed up by another chance encounter with the same duelist at the horse-market. A visit to the Temple enclosure, the Black Cross club, the Louvre, or the Knights of Saint John commandery in Marseilles all include the possibility of meeting this same character as well. Absent other factors, such as player choices or consequences arising out of a chance meeting, the character's appearance is governed by the roll of the dice, and his story in the actual play is a record of his interactions with the adventurers.

Some random encounters in the campaign are pretty straightforward; like Chris Miller, Mad Mesa's would-be gunslinger, they draw first and ask questions later, if at all. An encounter with a band of highwaymen on a King's Road, or a brawler in a tavern, doesn't need to be loaded down with deep connections - they are slices of life in the swashbucklers' world of the 17th century. There are no recurring characters, no additional chance meetings - once you've met Irving the Mad, Wild West homicidal maniac, you're unlikely to meet him twice . . . one way or the other. But some of these encounters also get slightly more involved backstories. An encounter with a drunken nobleman in a tavern may have a strand that connects him through his brother, a parish priest, back to Cardinal Richelieu - imagine Chris Miller's brothers coming to avenge his death. By giving even simple encounters a small backstory which reaches out into the setting, everything the adventurers do may carry unexpected, far-reaching consequences, for better or worse.

This week I'm going to look at the ways and means by which I create random encounters for Le Ballet de l'Acier, my Flashing Blades campaign. Tomorrow I'll begin by putting together a random encounter using the tables provided by Flashing Blades itself.

All news to me. Thanks, Mike.

ReplyDeleteAs usual, I learn something I needed to know to run a better game from you deciding to write up a detailed post on something that, to you and many others, is a Blinding Flash of the Obvious.

I suppose that makes me a Master of the Obvious, then?

DeleteReading forum discussions on random encounters suggests to me that it's not really all that obvious, though, as the linked thread shows. It seems to me that there are a lot of misconceptions about how random encounters can be used more effectively, even when all you start with is, Orcs (1-4).

Very cool. I've been thinking along similar lines recently.

ReplyDeleteI hope this was helpful.

DeleteRandom encounters are "strands in space leading off into the undiscovered portions of the game-world" and "part of the game-world delivery system." These are excellent descriptions and very much in line with my approach these days. I'm looking forward to reading the rest of this series.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Matthew - the first example is posted now.

DeleteGriffin Mountain is still my favorite Chaosium supplement (well I guess after the original Cults of Prax).

ReplyDeleteD&D Random Encounter tables actually gave me a very practical and personal example of how humans will try to link random events - that early practice is one reason that I never get attached to conspiracy theories in the RW. The other reason being a generally held belief that most people don't keep secrets well.

I recall frequently linking any two or three encounters I rolled as a DM back in the mid 1970s - e.g. roll Orcs for the first encoutner then Ogre for the second - presto! The Ogre is either the muscle or the big boss for the Orc Tribe.

I've heard it said that our ability to discern patterns from chaos is one of people's greatest abilities and worst faults at the same time.

DeleteI think I've said this before, but I fell in love with "chance encounters" when I started GMing Twilight:2000, back in the day. I would roll up encounters in advance of games, and then try to come up with at least a little variety and backstory on what they were up to, and how they could inform the players about the world.

ReplyDeleteFor example, this batch of soldiers was pretty disciplined, and had papers identifying their parent unit. But that batch of marauders wore mismatched uniforms, were low on ammunition, and had a sketch map of a few nearby towns, marked with targets for later hits.

{Hit publish too soon}. So, I am looking forward to more of this, and to try to build something more useful into some of my current games.

Delete"For example, this batch of soldiers was pretty disciplined, and had papers identifying their parent unit. But that batch of marauders wore mismatched uniforms, were low on ammunition, and had a sketch map of a few nearby towns, marked with targets for later hits."

DeleteAnd that's really all it takes - you could use the exact same stats for the members of each group, and yet each encounter will be memorable and distinctive, with opportunities and challenges arising from them.

I came to similar conclusions while reading an OSR hexrcawl. Some of the hex descriptions were very colorful, memorable, encounters that could easily be put into a Chance Encounters table.

ReplyDelete