"It's all fun and games until someone loses an eye. And a hand." - Vecna's momOne of the potential consequences of losing a fight in Flashing Blades is the prospect of suffering a debilitating wound. If a character is reduced to exactly zero hit points, the location of the final wound is used as the basis for determining if the character is temporarily or permanently disabled in some way. A character reduced to zero hit points by a wound on the head, frex, may lose a nose or an ear - both of which reduce the character's Charm attribute score - or receive a scar on a cheek - which increases the Charm attribute score! A wound to the chest may cause permanent internal injuries, reducing a character's Endurance attribute score, while a wound to a limb may result in a broken bone, which takes weeks to heal.

Flashing Blades' rules for recuperation also include the possibility of losing an eye, a hand, or a leg - a lost hand or leg can be replaced with a hook or a pegleg, respectively, and per the rules, a hook functions as a dagger, while a wooden leg limits the character to half-movement and proscribes both Lunge and Tackle attacks. A lost eye costs a point of Expertise from all martial skills, but this can be made up by normal experience as the character adjusts to the loss of peripheral vision and depth perception.

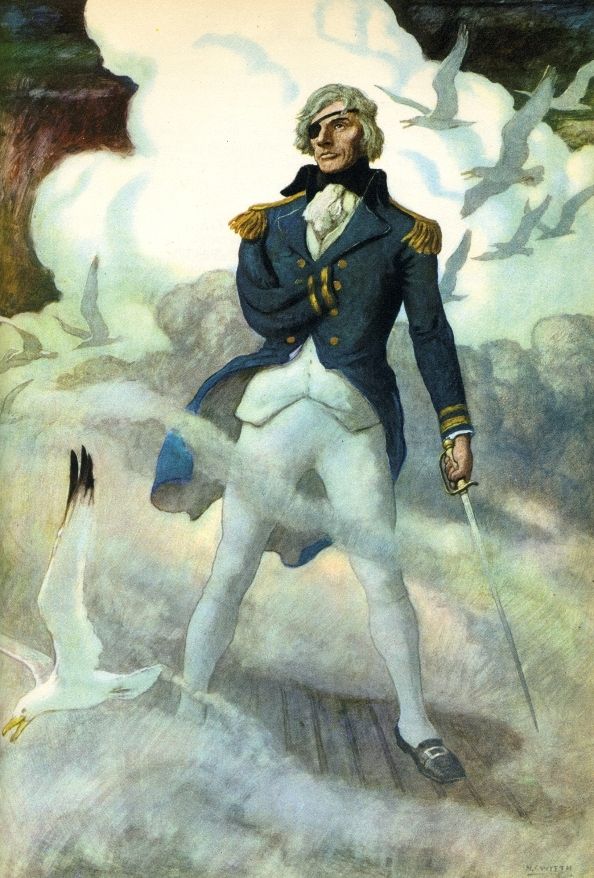

The popular image of the swashbuckler, particularly the pirate, with en eye-patch, a wooden leg, or a hook for a hand, is pretty common, but while it has a basis in history, such as Admiral Lord Nelson, it's surprisingly rare in cape-and-sword literature. Prosthetics such as wooden legs, hooks, and false eyes are well-documented in medical literature from the late Renaissance and Early Modern period, though as described in the writings of the famous French surgeon Ambroise Paré, they were often more elaborate than simple peg legs or hooks, shaped to resemble the actual missing limb and fitted with joints to provides some measure of use to the wearer. Paré even mentions a spring-equipped prosthetic hand, though it's unlikely that it was ever actually manufactured. That peg legs and hooks are so prevalent in pirate lore may reflect that the expertise required to create more life-like prosthetics was absent among most ship-board surgeons, resulting in the cruder examples with which most of us are familiar.

While wooden legs are reasonably well-documented in historical sources - the sixteenth century French buccaneer Francois le Clerc was nicknamed "Jambe de Bois" for his - hook hands are less well-known. The English privateer Christopher Newport reportedly received a hook as replacement for a lost hand; it's possible that Newport inspired the character of Captain Hook from J.M. Barrie's Peter Pan, one of the few fictional examples of a pirate with a hook-hand. Swashbucklers with peg-legs and eye-patches are just as uncommon, actually - the infamous and iconic "seafaring man with one leg" from RLS' Treasure Island, Long John Silver, doesn't have a peg-leg, relying instead on his crutch. In fact, it appears that the trope of the one-eyed, hook-handed, peg-legged pirate owes more to movies than to the literature on which they're based. Frex, the eye-patch worn by the comte de Rochefort in Richard Lester's Musketeers movies is the invention not of Alexandre Dumas but of Sir Christopher Lee, who wanted Rochefort to appear more menacing. The effect was so profound that both Michael Wincott and Mads Mikkelsen also portrayed Rochefort with an eye-patch in later movies as well.

The inclusion of lost eyes and limbs in Flashing Blades, then, appears to reflect the overt influence of cape-and-sword movies on the game's implied setting; it's an interesting design choice in light of the fact that so much of the game draws its inspiration from swashbuckling novels. While this wasn't unique to Flashing Blades - even 1e AD&D suggested that a character reduced to zero hit points "loses a limb, [or] is blinded in one eye" as an alternative to death - it presents players with the prospect of characters suffering a permanent disability while providing the specific rules for determining if and how that occurs and the effect on the character.

Over the years I've noticed a couple of schools of thought among players about character disability arising during play, as distinct from those players who choose disabilities during character creation as a means of gaining advantages elsewhere. One school asserts that 'death is boring,' that disability is a 'more interesting' alternative to losing one's character altogether. The other school claims that it's better that their characters die than be 'gimped' by the loss of attribute points or abilities. (There is also a school which wants neither, but I'm not going to give them any further consideration than to say, they're among us.)

My feeling is, let's have both. One of the reasons I like Flashing Blades is that both death and disability are on the table. They add the frisson of uncertainty when blades or guns are drawn to the experience of playing the game, and because they exist in the back of the players' minds, I think it adds to the characterisation which arises from actual play. One of the inherent tensions of the cape-and-sword genre comes from balancing the demands of honor with reckless violence - the decision to draw swords is, and in my opinion should be, a perilous one, and the risk of death or disability draws a big fat black line under that for me.

This seems like a rare case where the cinematic sources are more aligned with history than the literary sources. Usually it's the other way around.

ReplyDeleteI suspect that real pirates flaunted their scars, missing limbs and hook-hands since it added to their fearsome reputations. Like Sir Christopher, I wouldn't put it past a few them to don an eye-patch just for effect.

Inigo, the narrator of the Alatriste novels, does describe the captain's multiple scars in almost obsessive detail. But most of those scars are covered by his clothes -- I believe his only visible scar is over his left eyebrow. The scars do seem to add to the Captain's Charm (at least for Inigo!)

On the other side of the planet, the swashbuckling calvary officer Jiang Bin, one of the favorites of the Ming Dynasty Zhengde Emporer, took an arrow to face that came out through his ear, in a battle against brigands. He pulled it out and continued to fight. Upon hearing of this, the emperor was impressed. At his first audience with Jiang, the emperor saw the scars on Jiang's face and knew that the story was true. Later they became drinking buddies. So I guess the scars gave Jiang a Reaction Bonus -- at least with this particular emperor (who was enamored of warriors, Mongols in particular, to the point where he set up a yurt tent in the Forbidden City to sleep in, and engaged in all kinds of Mongol cosplay -- Ming LARPing?).

Anyway, fun post, Mike.

Thanks, Matthew. I was reading a biography of Ambroise Paré awhile back, and the horrific injuries which people survived, while nothing short of miraculous considering the state of care, must've left some terrible scars. In any case, I think FB's bonus for a scar on the face is an inspired nod to the genre.

DeleteI agree that both death and dismemberment add to the danger of combat, to the uncertainty. In Fictive Hack, there's a cool critical chart to determine if you are knocked out, dying, crippled, or dead, based on the severity of the critical roll when you run out of hit points. Then you can take "talents" to mitigate (but not dismiss) the effects of crippling.

ReplyDeleteThat's here: http://fictivefantasies.files.wordpress.com/2012/07/world-between-for-fictive-hack-11-12.pdf

Page 56.

Thanks for the link - looks brutal.

Delete